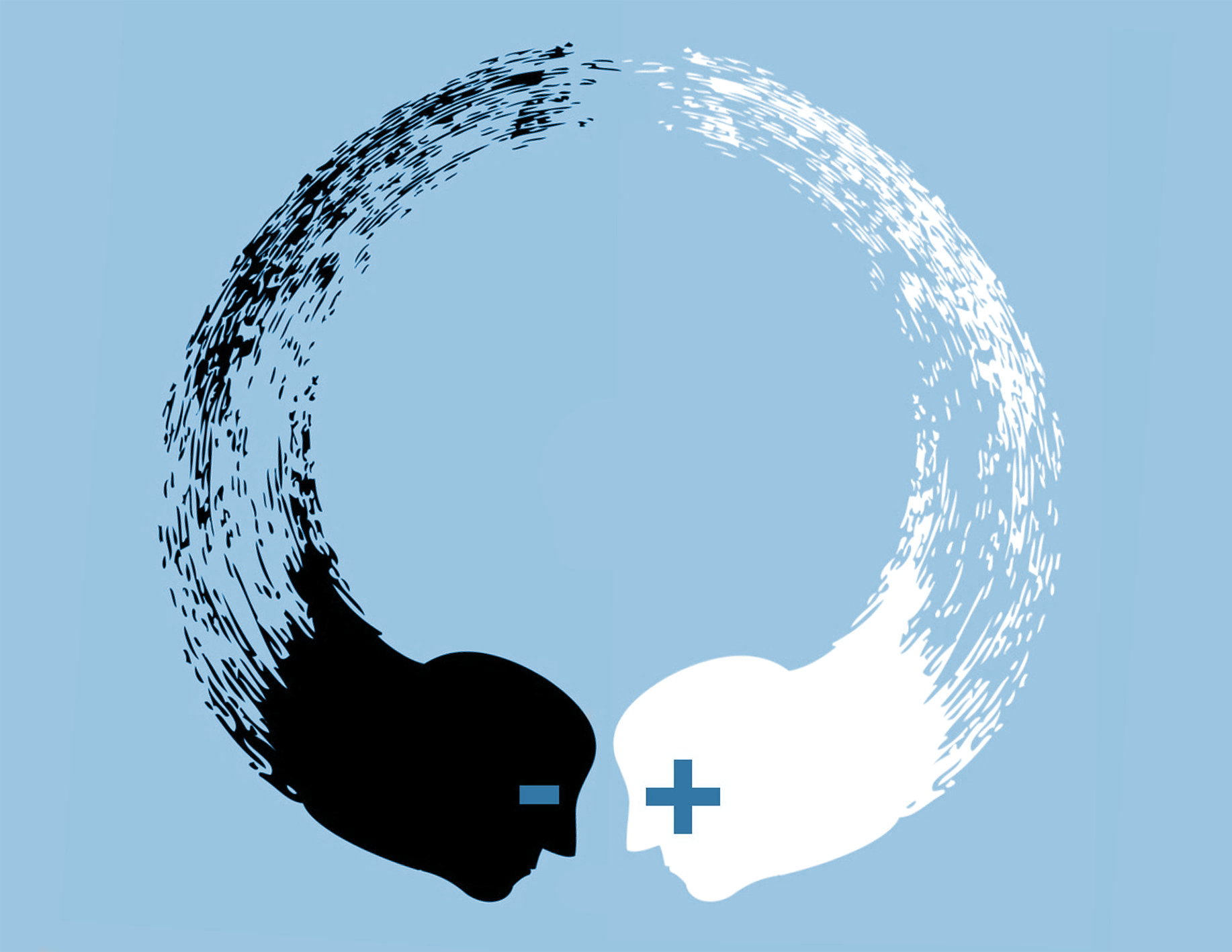

People always divide. We disagree about religion, politics, and how to store toothpaste. But polarization is more than division, and the Western world is more than divided right now.

Polarization has to do with the scope of division as well as how hastily we tend to divide. When I say that the West is polarized, I mean that many of us find ourselves at extreme ends of the spectrum on given issues and that we get ourselves there quickly (and, therefore, less thoughtfully).

We don’t just disagree significantly; we are quick to disagree and pick a side, especially when it comes to politics and other hot-button issues. In fact, it seems like each new issue gets politicized and splits us further and further apart.

In a word, polarization has made us more tribalistic. Our dividing lines are bolder, and our aversion to the other side much more intense.

It should come as no surprise that humans are tribalistic, for we all have a little tribalism in our nature. While most of us today only know the world as “nations” of millions of people, most of human history consisted of smaller groups that feuded with each other over land and resources. Sometimes, survival meant labelling the “other” tribe as inherently evil and therefore something to fear. That’s how you stayed safe. It worked.

The Path to Tribalism

Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff point out in their book The Coddling of the American Mind that harder times can bring out humanity’s tribalistic tendencies as we become sensitive to divisions and risks. It’s almost like a psychological switch that gets turned on. When things are safer, we’re relaxed and less sensitive to the differences we have with our neighbours. This allows larger human civilizations like nations and cities to exist since they can be built on trust.

However, when things seem less safe, we can tend towards a more reactive mindset and begin to think more in terms of “us vs. them.”

Interestingly, there is evidence that the presence of pathogens and parasites influences political attitudes towards authoritarianism. Yes, that means that the current COVID-19 pandemic may influence political belief. But it’s a sign of what’s deeper: humans have a built-in self-protection mode designed to raise sensitivity to potential dangers, whether that’s a pathogen or members of another tribe. The right circumstances switch these tribalistic tendencies on and shift our defences into high gear.

Haidt and Lukianoff point out that social media no doubt helps the process. Just like cable news before it, social media outlets want our attention. One of the best ways to do that is through exploiting our negativity bias.

Naturally, broadcasters and influencers want to shape your worldview and keep eyeballs glued to screens. Therefore, they’ll leave out the good or exaggerate the bad in the stories they tell. In doing so, they make us more sensitive to the bad.

This makes those who differ from us seem worse than they are. It makes their worldviews seem like they have far worse implications than they probably do.

It makes us want to suppress, run away from, or otherwise do away with perspectives or ideas that we perceive to be dangerous.

Hence, polarization. And it happens on both sides of the aisle. Though, admittedly, most media and big tech companies that control today’s news flow are liberally inclined.

And when you only hear one side of a story, polarization fuels yet further.

Concept Creep and How Our Brains Make Categories

Another contributor to polarization and tribalism involves how our brains categorize observed phenomena.

When one category is particularly small, the brain is more likely to re-categorize data in order to make the category more meaningful. (I get this from Daniel Levitin’s book Successful Aging – he notes that as we age, we are more likely to do this, but it happens at all ages.)

Let’s say that the number of violent crimes in your city vastly decreases. Your category, “violent crimes,” then shrinks to the point of becoming meaningless, since you rarely see any violence around you.

To compensate, your brain starts to see more things as violent. So, where before only things like rape, murder and assault fit under “violent crimes,” now you might include offensive language.

Whether directly related to this phenomenon of category-shift or not, Haidt and Lukianoff note that a “concept creep” has occurred with ideas like microaggressions. Only years ago, our categories for “aggression” or even “violence” had a much higher threshold. Today, masses of people consider accidental racist remarks as “aggressions” and even “violence.”

Peace has changed how we categorize conflict.

Growing Pains

It’s important to note that while internal categorization has changed, the exact nature of violence has not. We don’t get to move the goalposts, even if things like peaceful living, social media, etc., are playing some psychological tricks on us.

Who knows? Maybe this is just how society goes. Perhaps in our future we’ll be such a peaceful race that, indeed, verbal assault will be considered on par with physical violence. Maybe category shifts are part of our greater evolution.

I tend to think we ought to err on the side of giving the benefit of the doubt and holding out grace for those who make mistakes. We don’t want to become the world of Minority Report, dishing out punishments for crimes not committed.

The stability of the modern world is built on trust and fairness, innocence until proven guilty, freedom to speak your mind, and so on. Erode freedom and trust with a perfectionistic morality and lack of grace, and eventually, everything crumbles.

In fact, it’s already begun. Many of us fear defending friends or colleagues or challenging certain ideas, lest the mob come to lynch us.

That’s not the sign of a healthy society; it’s a sign of tribalism and divisiveness.

And now we’re nearly back to where we started.

So begins the spiral.